Singtam could sink in major quake, says expert as Sikkim faces seismic danger

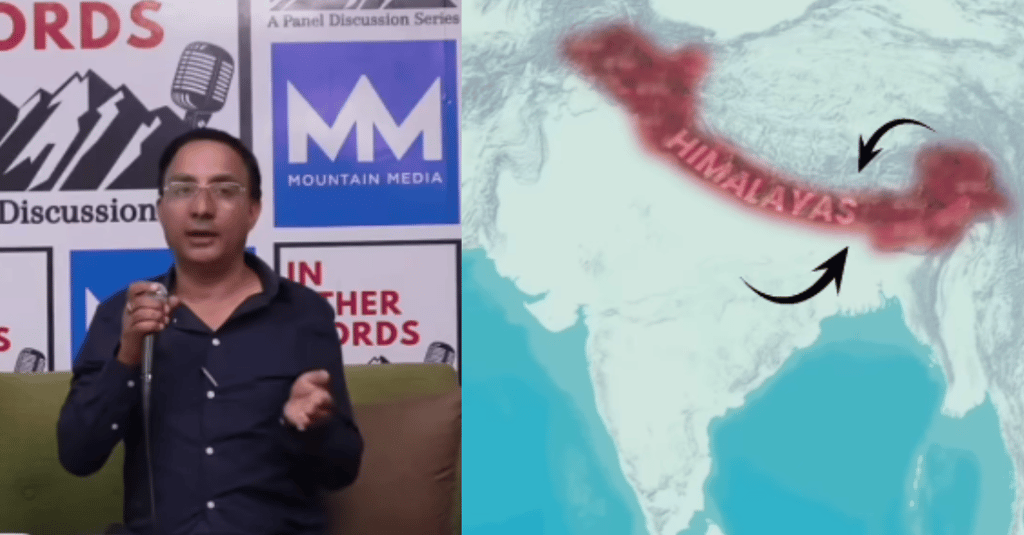

Explaining the region’s natural vulnerability, Khanal said that the Sikkim Himalayas were formed due to the continuous movement of the Indian and Tibetan tectonic plates.

LOCAL

Renowned geologist G.C. Khanal has raised concerns about the rising risk of earthquakes in Sikkim urging authorities to rely on local experts for disaster preparedness rather than depending solely on foreign studies and systems.

Explaining the region’s natural vulnerability, Khanal said that the Sikkim Himalayas were formed due to the continuous movement of the Indian and Tibetan tectonic plates. “These plates are still in motion, shifting at a rate of 3 to 5 centimetres every year. As a result, the mountains are rising by around 3 to 10 millimetres per year,” he said. This ongoing movement makes the entire region naturally prone to seismic activity.

Khanal warned that if a strong earthquake hits Sikkim, the impact could vary sharply from place to place. “Gangtok may not be severely affected because it sits on strong geological formations. But other places like Siksepati could behave very differently during a quake,” he said.

One of the most alarming revelations came in reference to Singtam, a town located along the banks of the Teesta River. “If an earthquake hits in Singtam, the town could completely sink. That area is extremely fragile and vulnerable,” Khanal said.

He further pointed out the current overdependence on international organisations for seismic studies and disaster preparedness plans. While acknowledging the assistance of agencies like German and Swiss cooperation, he questioned the practical outcomes of their studies. “They come, conduct studies, and leave. We are not sure what they are doing, and once their systems are installed, we don’t know how they work or where to seek help if something goes wrong,” he said.

A particular concern was the early warning systems provided by international agencies. Khanal warned that even a small technical defect in such systems could prove dangerous. “When something goes wrong, they are not there. We don’t know who to contact. So we must rely on real experts who are available on the ground and can work with us in disaster mitigation,” he said.

His remarks come at a time when the Himalayan belt, including Sikkim has been under increased observation due to frequent tremors reported across the region. Khanal’s statement is a wake-up call for both the government and the public to act before disaster strikes.

Disaster management in mountain regions like Sikkim requires continuous monitoring, proper infrastructure planning and most importantly, expert involvement. Khanal has urged policymakers to invest in locally-based scientific research, proper land-use regulations and public awareness campaigns to prepare for any possible future quake.